Performing the hip replacement operation from the anterior approach has a few advantages.

- It allows the surgeon to do X-rays during surgery. Conventional hip replacement surgery is done without using xrays during surgery.

- Allows surgeon to preserve posterior capsule and muscle, decreasing risk of dislocation.

- Allows surgeon to preserve hip abductors. Dysfunction of the abductor would cause prolonged, if painless, limping.

Recovery after anterior hip replacement is a little quicker, but the ultimate outcome is not better compared to the posterior approach.

What are the other approaches to the hip?

In order to perform a hip replacement, the hip joint can be approached in several different ways:

- Transtrochanteric approach

- Posterior approach: also known as transgluteal approach, as well as posterolateral approach.

- The anterolateral approach: also known as the lateral approach, or sometimes as the Hardinge approach.

- The direct anterior approach, known also as the Smith-Petersen, or Hueter approach.

A little bit of history

Hip replacement operations have been done successfully since the 1960's. Dr John Charnley, in England, was the first to routinely perform successful hip replacements. His basic idea remains valid to this day: a metallic ball that articulates with a polyethylene socket.

His approach to the hip was transtrochanteric. He performed an osteotomy of the greater trochanter of the femur in order to get into the hip joint. After the surgery, the osteotomized trochanter had to be allowed to heal for several months.

Glossary

Osteotomy = Cutting of bone. This is done with saws, chisels, and other such tools. Trochanter = rough prominence of bone in the femur that serves as attachment for the hip abductor muscles.

Current artificial hip joints are similar to those first implanted by Dr Charnley in that they are made of a metal ball and a polyethylene socket. However, the method of insertion is rarely the same. Although a trochanteric osteotomy is sometimes needed for a revision surgery, an uncomplicated hip replacement is nowadays almost never done via a transtrochanteric approach. Instead the surgeons go either in front or behind the trochanter of the femur. The two common current approaches therefore are the anterolateral or Hardinge approach, and the posterior approach.

Is there a problem with the posterior and with the anterolateral approaches?

The posterior approach is a very good approach, in that it preserves the hip abductors and does not cause as much limping as the anterolateral approach. The problem with the posterior approach is that it has a statistically higher dislocation rate.

The other commonly performed hip approach, the anterolateral approach, has a statistically lower dislocation risk. The anterolateral approach's major problem is prolonged limping after surgery. Patients sometimes limp for a year, sometimes for ever, when this could have been avoided.

The anterior approach

The anterior approach presumes to avoid the limping of the anterolateral approach, at the same time keeping the dislocation rate lower than the posterior approach. The direct anterior approach has been popularized by Dr Joel Matta, who is perhaps the most experienced acetabular and pelvic orthopedic surgeon in the US.

The direct approach implies going between (as opposed to through) the muscles and the tendons of the hip. This approach therefore has been called muscle sparing.

It is important to understand that while the anterior approach for a hip replacement can be done safely, it is not necessary for a good hip replacement operation.

How is this operation done?

I use the Hana orthopedic traction table during this operation.

The patient is positioned with the legs secured in "ski boot" holders. The table allows secure manipulation and appropriate positioning of the left during the surgery.

The table allows safe manipulation of the hip joint. In addition, duing surgery patient is positioned flat on his or her back, and it is easy to get good xrays and confirm position of the prosthesis before surgery is over.

While the incision is smaller and the muscles are treated with more respect, the rest of the operation is still the same: power saws and power reamers are used inside the body to cut and shape the bones for the artificial implant: In the picture below the tool in my left hand is a sterile power saw. I was doing a right hip replacement. This instrument is not too different from the Dremel tools that you can buy at the home improvement store.

Here's a picture of an arthritic eburnated femoral head that has been cut out, soon to be replaced with an artificial piece.

Again, a major advantage, at least the way I see it, is that the procedure is performed with the patient on his or her back, allowing the surgeon to use xray during surgery. For instance, in the picture below, as I am inserting the acetabular cup, I can see that I need to slightly adjust the position of the acetabular component.

Case study #1

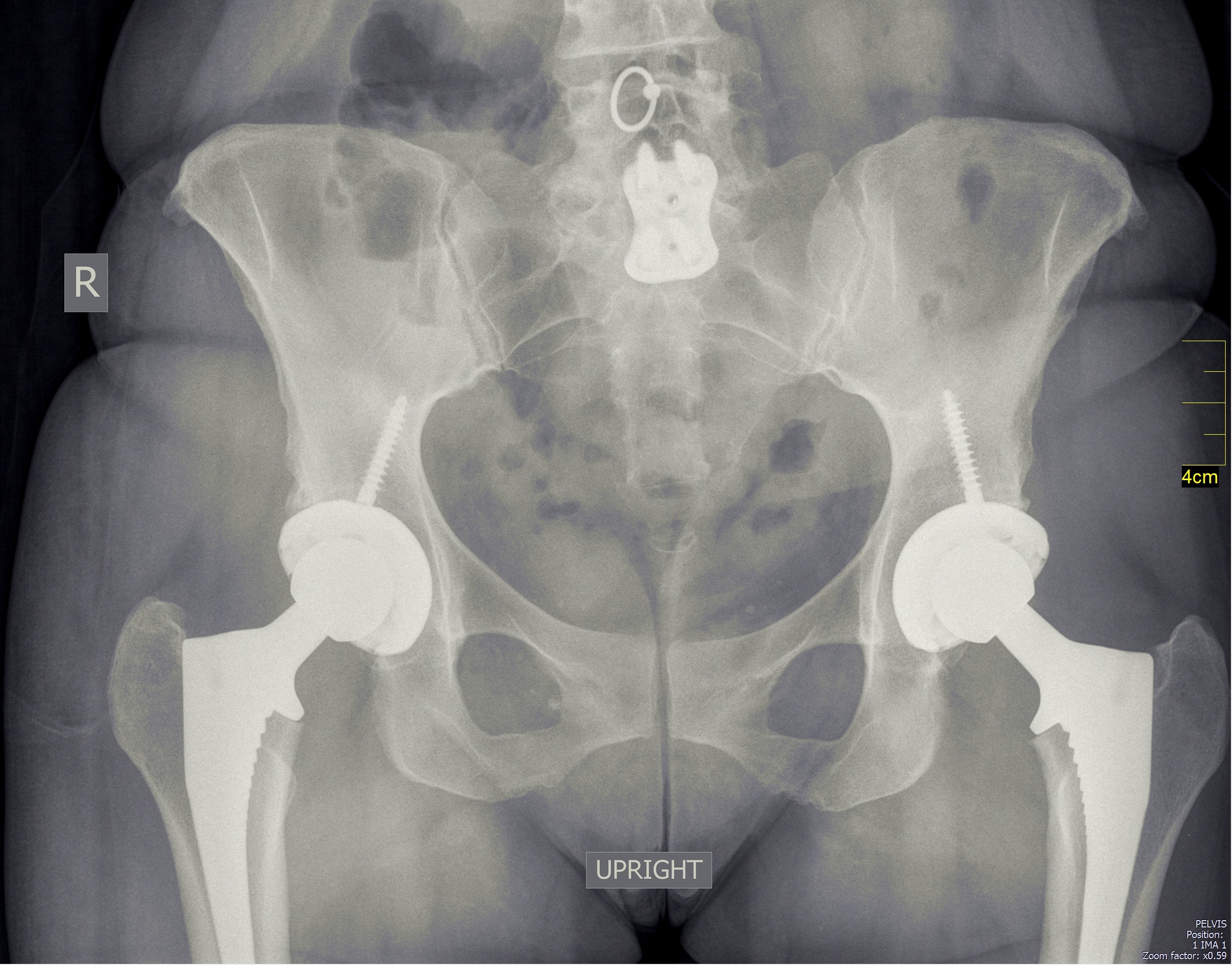

Since the patient is supine, it is possible to perform bilateral simultaneous hip replacements. Here's the appearance of a patient who had both hips replaced:

Video at 2 weeks

This is a video of a different patient 2 weeks after hip replacement.

It is important to remember that for the full potential of this operation to be realized, the patient should be relatively fit, and healthy. The muscles around the hip should be in good shape, heart and lungs should also be relatively healthy. This operation is a hip replacement and a hip replacement only, and it will not cure the other ailments that may be contributing to a patient's immobility.